Sometimes a work of art is so familiar you don't really look at it very closely, and then when you do, you realize you never really looked at it that carefully in the first place.

Reading Kirk Varnedoe's A Fine Disregard, I came across an interesting essay on Rodin's Burghers of Calais. He's a little hard to summarize because he always supplies quite a lot of background and context, but I'll do my best:

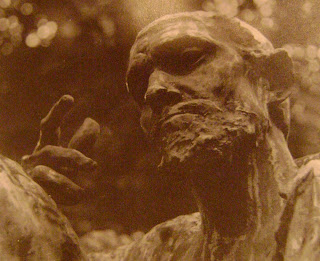

Varnedoe says that Rodin did nothing to hide the artificiality of his art. Joint lines show and marks of modeling are not hidden in any way. He often made up scores of "spare parts" he used to put together figures: hands, feet, knees, etc. "Such physical, literal instances of sculptural fragmentation and repetition in Rodin negated basic conventions of wholeness, illusionism, and narration.. . In one way of thinking, it is precisely this split between content and form that makes Rodin's work modern.

With the Burghers of Calais, Rodin took a medieval story familiar to all schoolchildren of the time, of how six citizens volunteer to be sacrificial hostages to an English king in order to end of long, wartime seige. As Varnedoe explains, "Dissatisfied with the old conventions of summing up such a story in one hero or rhe

torical gesture, he decided that, to get at the truth of what happened, the monument should treat all six equally. To do that, he tried to "imagine the moment of commitment when the victims prepared to march out to what seemed certain death, decomposed the even, conceptually and practically, into the smallest bits." (p. 133)

torical gesture, he decided that, to get at the truth of what happened, the monument should treat all six equally. To do that, he tried to "imagine the moment of commitment when the victims prepared to march out to what seemed certain death, decomposed the even, conceptually and practically, into the smallest bits." (p. 133)"He studied not just every man, but every arm, every hand, and even every finer, as an individualy entity, in order to build up an atomized repertoire of discrete units of expression."

Making sense so far? So he has this "lavish palette of recombinant possibilities" and what does he do? Something strange. I never noticed this til now, but two of the figures have the same head, and a third has that same face, only slightly altered. The same fingers appear on several figures, and when Rodin put the

whole thing together he did nothing to try to link them by gestures or glances. They are also all sitting on different bases, but their heads are all level (when a more common set-up would have been a pyramidal arrangement).

whole thing together he did nothing to try to link them by gestures or glances. They are also all sitting on different bases, but their heads are all level (when a more common set-up would have been a pyramidal arrangement).Varnedoe makes his case that Rodin's decisions stem from his conception of the meaning of this event. These are people caught in various stages of unresolved inner struggle, trapped in private agonies of regret, isolated from one another as they search their minds. But the recurrent parts, suggest that these victims are also part of a collective, and so interchangeable and similar in certain ways. Of course the monument also calls to mind the struggle between the sense of public duty at war with the individual's own private will. (p. 138-9)

As usual, Varnedoe has a LOT more to say, but I think this is enough to get a feeling for his thoughts on how artists play with possibilities, in this case fragmentation and repetition, and from this trying out of forms in new contexts, find new ways to model the world.

I guess maybe all these plastic Polly Pocket and Barbie parts on the floor here at home could find new uses, but new meaning? Not so sure about that.

No comments:

Post a Comment